Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 9; Partly cited in: The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Macropaedia (19 v.) Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1983. p. 514

Contesto: At present the fashion appears to have set in in favour of two very distinct styles. One is a very impure and bastard Italian, which is used in most large secular buildings; and the other is a variety of the architecture of the thirteenth century, often, I am sorry to say, not much purer than its rival, especially in the domestic examples, although its use is principally confined to ecclesiastical edifices. It is needless to say that the details of these two styles are as different from each other as light from darkness, but still we are expected to master both of them. But it is most sincerely to be hoped that in course of time one or both of them will disappear, and that we may get something of our own of which we need not be ashamed. This may, perhaps, take place in the twentieth century, it certainly, as far as I can see, will not occur in the nineteenth.

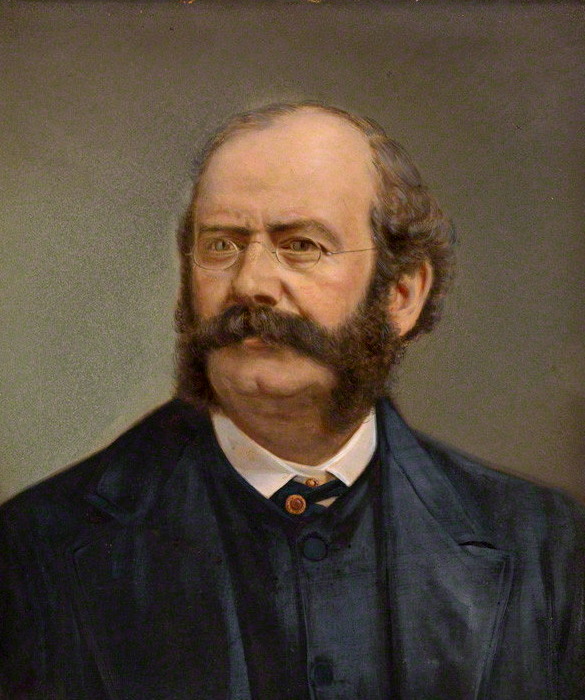

William Burges: Frasi in inglese

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 1 : Preface

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 2

Attributed to William Burges (1860) paper on architectural drawing in: Sir Reginald Theodore Blomfield (1912) Architectural drawing and draughtsmen https://archive.org/stream/cu31924015419991#page/n25/mode/2up, Cassell & company, limited, 1912. p. 6-7

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 71; Partly cited in: Export of objects of cultural interest 2010/11: 1 May 2010 - 30 April 2011. Stationery Office, 13 dec. 2011

Quote was introduced with the phrase:

In the lecture on the weaver's art, we are reminded of the superiority of Indian muslins and Chinese and Persian carpets, and the gorgeous costumes of the middle ages are contrasted with our own dark ungraceful garments. The Cufic inscriptions that have so perplexed antiquaries, were introduced with the rich Eastern stuffs so much sought after by the wealthy class, and though, as Mr. Burges observes

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 85; Cited in: " Belles Lettres http://books.google.com/books?id=0EegAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA143" in: The Westminster Review, Vol. 84-85. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1865. p. 143

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 1 : Preface

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 1

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 13

“The real mission of machinery is to reduce pounds to shillings and shillings to pence.”

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 2

William Burges, Architectural Drawings, London, 1870. p. 1; As cited in American Architect and Building News. 1881. Vol. 9. p. 236

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 8-9; Partly cited in: Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. Vol. 99. 1951. p. 520

“The civil engineer is the real 19th century architect.”

William Burges in: The Ecclesiologist, Vol. 28, 1867, p. 156: Cited in Crook (2004)

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 8

Eastop & Gil commented that:

Burges held strong views about furniture, and protested at the "enormities, inconveniences, and upholsterers." (1865: 69) He advocated the use of the medieval style, because "not only did its duty as furniture, but spoke and told a story" (1865: 71).

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 69: Partly cited in: Dinah Eastop, Kathryn Gill (2012) Upholstery Conservation: Principles and Practice. http://books.google.com/books?id=2gf50OiP8lAC&pg=PA50 p. 47.

William Burges "Art and Religion", in: The Church and the World: Essays on Questions of the Day, Orby Shipley ed., London, 1868, pp. 574-98; As cited in: John Pemble. Venice rediscovered. Clarendon Press, 16 mrt. 1995. p. 133

“I have been brought up in the 13th century belief, and in that belief I intend to die.”

William Burges The Builder, Vol 34, 1876, p. 18: Cited in: Peter Galloway, The cathedrals of Ireland, 1992, p. 62; Also cited in Crook (2004)

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 1 : Preface

Origine: Art applied to industry: a series of lectures, 1865, p. 91-92; Cited in: "William Burges 1827-1881 London Architect" in: In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement http://books.google.com/books?id=56F8Qv96FzwC&pg=PA406. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 jan. 1986. p. 405

J. Mordaunt Crook, " Burges, William (1827–1881) http://www.oxforddnb.com/templates/article.jsp?articleid=3972&back=&version=2004-09", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004