“A Court of equity knows its own province.”

Mayor, &c. of Southampton v. Graves (1800), 8 T. R. 592.

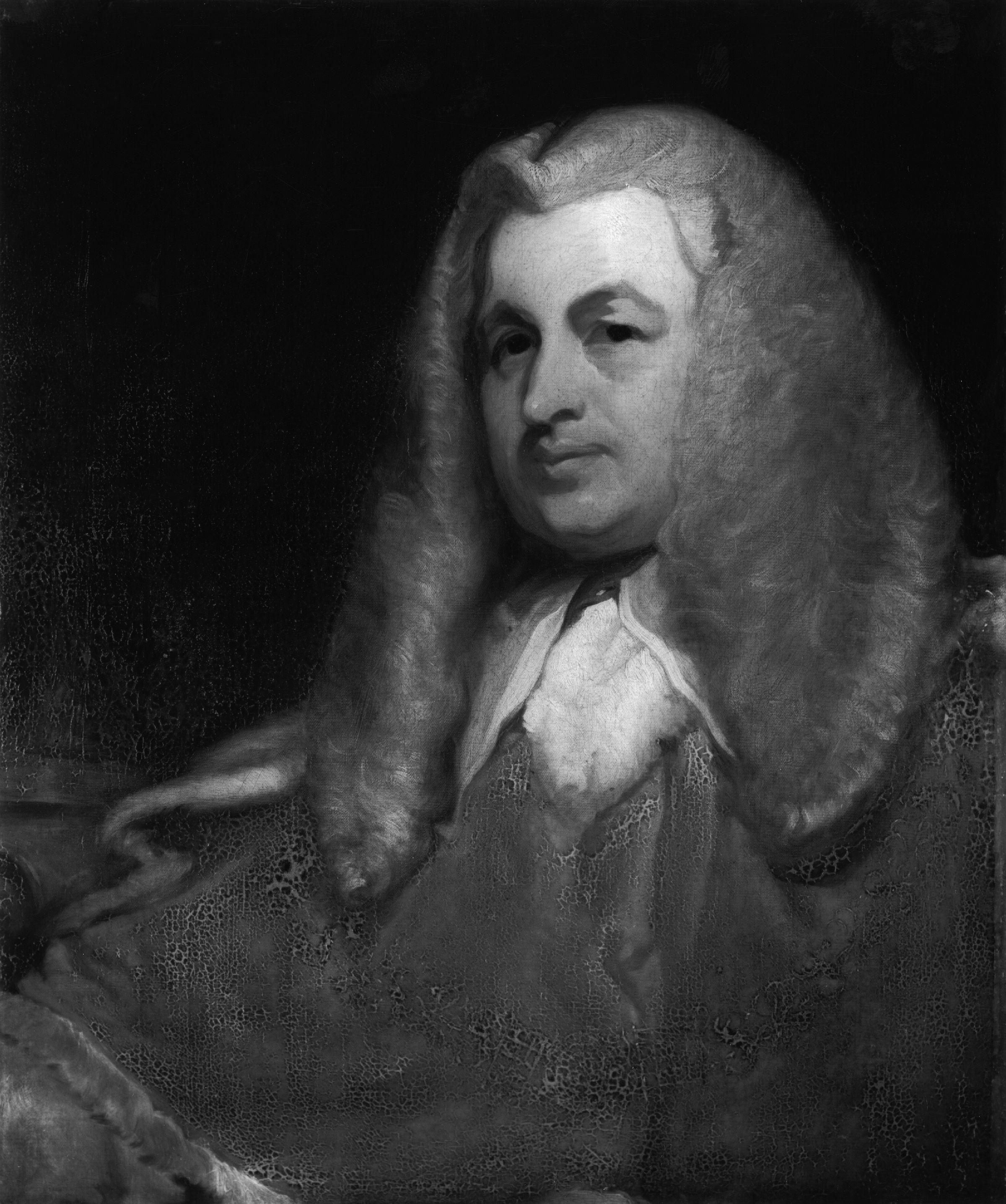

Lloyd Kenyon, 1st Baron Kenyon, , was a British politician and barrister, who served as Attorney General, Master of the Rolls and Lord Chief Justice. Born to a country gentleman, he was initially educated in Hanmer before moving to Ruthin School aged 12. Rather than going to university he instead worked as a clerk to an attorney, joining the Middle Temple in 1750 and being called to the Bar in 1756. Initially almost unemployed due to the lack of education and contacts which a university education would have provided, his business increased thanks to his friendships with John Dunning, who, overwhelmed with cases, allowed Kenyon to work many, and Lord Thurlow who secured for him the Chief Justiceship of Chester in 1780. He was returned as the Member of Parliament for Hindon the same year, serving repeatedly as Attorney General under William Pitt the Younger. He effectively sacrificed his political career in 1784 to challenge the ballot of Charles James Fox, and was rewarded with a baronetcy; from then on he did not speak in the House of Commons, despite remaining an MP.

On 27 March 1784, he was appointed Master of the Rolls, a job to which he dedicated himself once he ceased to act as an MP. He had previously practised in the Court of Chancery, and although unfamiliar with Roman law was highly efficient; Lord Eldon said "I am mistaken if, after I am gone, the Chancery Records do not prove that if I have decided more than any of my predecessors in the same period of time, Sir Lloyd Kenyon beat us all". On 9 June 1788, Kenyon succeeded Lord Mansfield as Lord Chief Justice, and was granted a barony. Although not rated as highly as his predecessor, his work "restored the simplicity and rigor of the common law". He remained Lord Chief Justice until his death in 1802.

Wikipedia

“A Court of equity knows its own province.”

Mayor, &c. of Southampton v. Graves (1800), 8 T. R. 592.

The King v. Inhabitants of St. Paul's, Bedford (1797), 6 T. R. 454.

Trial of John Vint and others (1799), 27 How. St. Tr. 640.

“What a man does in his closet ought not to affect the rights of third persons.”

Outram v. Morewood (1793), 5 T. R. 123.

Holt's Case (1793), 22 How. St. Tr. 1234.

Clayton v. Adams (1796), 6 T. R. 605.

“Sitting in a Court of law, I can receive no evidence but what comes under the sanction of an oath.”

Wright v. Barnard (1797), 2 Esp. 701.

King v. The College of Physicians (1797), 7 T. R. 288.

Bradley and another v. Clark (1793), 5 T. R. 201.

“Some modern cases have in my opinion gone too far.”

Walford v. Duchess de Pienne (1797), 2 Esp. 555.

Case of John Lambert and others (1793), 22 How. St. Tr. 1018.

Reeves' Case (1796), 26 How. St. Tr. 591.

R. v. Inhabitants of Darlington (1792), 4 T. R. 800.

Pasley v. Freeman (1789), 3 T. R. 51.

“That corporations are the creatures of the Crown must be universally admitted.”

King v. Ginever (1796), 6 T. R. 735.

“Modus in rebus—there must be an end of things.”

Proceedings against the Dean of St. Asaph (1783), 21 How. St. Tr. 875.

Wilson v. Marryat (1798), 8 T. R. 44.

The King v. Justices of Surrey (1794), 6 T. R. 78.

“In the hurry of business, the most able Judges are liable to err.”

Cotton v. Thurland (1793), 5 T. R. 409.

Trial of John Vint and others (1799), 27 How. St. Tr. 640.

“We ought not to decide hastily against the words of an Act of Parliament.”

King v. Justices of Flintshire (1797), 7 T. R. 200.

Trial of the Earl of Thanet, and others (1799), 27 How. St. Tr. 940.