“[A Keith Jarrett] Lo sai perché non suono più ballads? Perché mi piace moltissimo suonare ballads!”

citato in Ian Carr, Keith Jarrett: l'uomo, la musica, Arcana Editrice, 1992

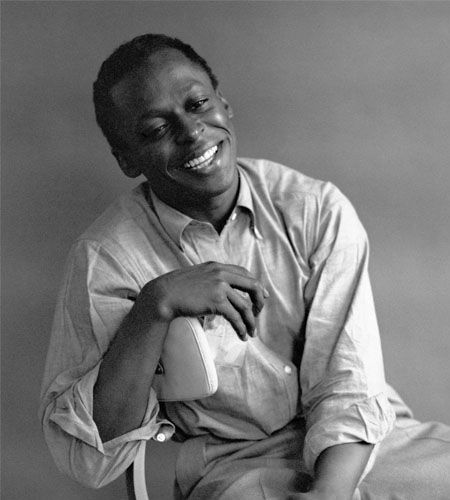

Miles Dewey Davis III è stato un compositore e trombettista statunitense jazz, considerato uno dei più influenti, innovativi ed originali musicisti del XX secolo.

È difficile non riconoscere a Davis un ruolo di innovatore e genio musicale. Dotato di uno stile inconfondibile ed un'incomparabile gamma espressiva, per quasi trent'anni Miles Davis è stato una figura chiave del jazz e della musica popolare del XX secolo in generale.

Dopo aver preso parte alla rivoluzione bebop, egli fu ideatore di numerosi stili jazz, fra cui il cool jazz, l'hard bop, il modal jazz e il jazz elettrico o jazz-rock. Le sue registrazioni, assieme agli spettacoli dal vivo dei numerosi gruppi guidati da lui stesso, furono fondamentali per lo sviluppo artistico del jazz.

Miles Davis fu e resta famoso sia come strumentista dalle sonorità inconfondibilmente languide e melodiche, sia per il suo atteggiamento innovatore , sia per la sua figura di personaggio pubblico. Fu il suo un caso abbastanza raro in campo jazzistico: fu infatti uno dei pochi jazzmen in grado di realizzare anche commercialmente il proprio potenziale artistico e forse l'ultimo ad avere anche un profilo di star dell'industria musicale. Una conferma della sua poliedrica personalità artistica fu la sua ammissione, nel marzo 2006, alla Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; un ulteriore riconoscimento di un talento che influenzò tutti i generi di musica popolare della seconda metà del XX secolo.

L'opera di capo orchestra di Davis è importante almeno quanto la musica che produsse in prima persona. I musicisti che lavorarono nelle sue formazioni, quando non toccarono l'apice della carriera al fianco di Miles, quasi invariabilmente raggiunsero sotto la sua guida la piena maturità e trovarono l'ispirazione per slanciarsi verso traguardi di valore assoluto.

Dotato di una personalità notoriamente laconica e difficile, spesso scontrosa, Davis era anche per questo chiamato il principe delle tenebre, soprannome che alludeva fra l'altro alla qualità notturna di molta della sua musica. Questa immagine oscura era accentuata anche dalla sua voce roca e raschiante . Chi lo conobbe da vicino descrive una persona timida, gentile e spesso insicura, che utilizzava l'aggressività come difesa.

Il Davis strumentista non fu un virtuoso nel senso in cui lo furono, ad esempio, Dizzy Gillespie e Clifford Brown. Egli è tuttavia considerato da molti uno dei più grandi trombettisti jazz, non solo per la forza innovatrice della composizione, ma anche per il suo suono - che divenne praticamente un marchio di fabbrica - e l'emotività controllata caratteristica della sua personalità solistica, che in dischi come Kind of Blue trova forse la sua massima espressione. La sua influenza sugli altri trombettisti fa di Miles Davis un personaggio chiave nella storia della tromba jazz, al pari di Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie, Clifford Brown, Don Cherry e altri ancora.

Davis fu un vero laboratorio vivente che consentì non solo lo sviluppo di generazioni di musicisti e di nuove tendenze musicali, ma lasciò traccia anche nel costume. Lasciandosi a volte guidare dal pubblico, e a volte precedendolo, egli non esitò mai a reinventare il suono e la musica per cui era conosciuto, nemmeno dopo il successo del rock, quando passò ad una sonorità totalmente elettrica, sfidando l'opposizione e talvolta l'ostilità della critica. Il grande carisma dell'uomo, oltre che da un'enorme produzione artistica di indiscusso valore, scaturì anche da un'attenta costruzione dell'immagine, opportunamente e sapientemente aggiornata nel corso degli anni, sino ad arrivare all'ultimo periodo in cui il vestiario pieno di colore conferiva una certa sacralità e ritualità alle peculiari esibizioni dell'unico musicista del XX secolo che seppe essere allo stesso tempo artista rivoluzionario e icona della cultura pop, dell'industria dello spettacolo e dei megaconcerti.

Wikipedia

“[A Keith Jarrett] Lo sai perché non suono più ballads? Perché mi piace moltissimo suonare ballads!”

citato in Ian Carr, Keith Jarrett: l'uomo, la musica, Arcana Editrice, 1992

dal DVD Miles in Paris – 1989

dal DVD Miles in Paris – 1989

“Per me la musica e la vita sono una questione di stile.”

Miles: l'autobiografia di un mito del jazz

Miles: l'autobiografia di un mito del jazz

Miles: l'autobiografia di un mito del jazz

“He plays like somebody is standing on his foot.”

Alternative: He plays like somebody was standing on his foot.

In Down Beat "Blindfold Test" with Leonard Feather (13 June 1964); also in

On Eric Dolphy

1960s

During an interview, after growing aggravated about questions on the subject of race.

1980s

Origine: Jet (25 March 1985)

Robert Fripp, on how Miles Davis influenced his leadership in King Crimson.

As quoted in a Rolling Stone interview "The Crimson King Seeks a New Court" by Hank Shteamer (15 April 2019) https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/robert-fripp-interview-king-crimson-tour-david-bowie-kanye-west-820783/.

Quotes by others

“Don't play what's there, play what's not there.”

In SPIN (December 1990). p. 30, and in many other sources https://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&hl=en&q=%22play+anything+on+a+horn%22+miles+davis#hl=en&q=%22don%27t+play+what%27s+there%22+not+davis&tbm=bks, but I can't find the original one.

1990s

“For me, music and life are all about style.”

Miles, the Autobiography (1989) (co-written with Quincy Troupe, p. 398.)

1980s

“Is that what you wanted, Alfred?”

Quoted in: Jazz Journal International, (1983), p. 12.

Miles Davis asking Blue Note records producer Alfred Lion's approval of a recorded performance in Rudy Van Gelder's studio. Miles' gravelly-voice question was accidentally recorded, but included at the end of "One For Daddy-O" on the Cannonball Adderley recording "Somethin' Else": a famous recorded peek into the recording studio process.

1980s

“He could very well be the Duke Ellington of Rock 'n' Roll.”

In [A Change is Gonna Come: Music, Race & the Soul of America, Craig Hansen, Werner, University of Michigan Press, 2006, 9780472031474, 53] as: he can be the Duke Ellington of our times.

And in [Miles on Miles: Interviews and Encounters with Miles Davis, Musicians in Their Own Words Series, Paul Maher, Michael K. Dorr, Chicago Review Press, 2009, 9781556527067, 262] as: Do you know who Prince kinda reminds me of, particularly as a piano player? Duke! Yeah, he's the Duke Ellington of the eighties to my way of thinking.

On Prince

2000s

In the Jazz Review with Nat Hentoff (1958); also in , and in many other books https://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&hl=en&q=%22play+anything+on+a+horn%22+miles+davis

On Louis Armstrong in a Playboy magazine interview.

1950s

As quoted in Jazz-Rock Fusion: The People, The Music, p. 40

1970s

As quoted in Jazz-Rock Fusion: The People, The Music (1978) by Julie Coryell and Laura Friedman, p. 40

1970s

“My ego only needs a good rhythm section.”

In [Milestones: The music and times of Miles Davis since 1960, Jack, Chambers, Beech Tree Books, 1983, 9780688046460, 261]

"My ego only needs a good rhythm section" is also the title of an interview/article by Stephen Davis for The Real Paper (21 March 1973)

On being asked what he looked for in musicians.

1970s

“A legend is an old man with a cane known for what he used to do. I'm still doing it.”

On being called a legend.

Quoted in International Herald Tribune (17 July 1991); also in: [The Yale Book of Quotations, Fred R., Shapiro, Yale University Press, 2006, 9780300107982, 189]

1990s

“I’ll play it and tell you what it is later.”

In [So What: The Life of Miles Davis, John, Szwed, Random House, 2012, 9781448106462], and in many other books https://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&hl=en&q=%22play+anything+on+a+horn%22+miles+davis#hl=en&q=%22+and+tell+you+what+it+is+later.+%22+miles+davis&tbm=bks

Sometimes rendered as: I'll play it first and tell you what it is later.

During a recording session for Prestige, on the album "Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet" (1956).

1950s

Bill Evans, on about Miles Davis's change of style to jazz fusion.

http://jazztimes.com/articles/20128-miles-davis-and-bill-evans-miles-and-bill-in-black-white.

Quotes by others

As quoted in Jazz-Rock Fusion: The People, The Music, p. 40

1970s

“I've changed music four or five times. What have you done of any importance other than be white?”

Miles, the Autobiography (1989) (co-written with Quincy Troupe, p. 371.)

At a White House reception in honor of Ray Charles 1987, this was his reply to a society lady seated next to him who had asked what he had done to be invited.

1980s

In Playboy to Alex Haley (1962); also in [Milestones: The music and times of Miles Davis since 1960, Jack, Chambers, Beech Tree Books, 1983, 9780688046460, 209], [The Playboy Interviews, Alex, Haley, Murray, Fisher, Ballantine, 1993, 9780345383006, 15], [The Miles Davis companion: four decades of commentary, Gary, Carner, Gary, Carner, Schirmer Books, 1996, 9780028646121, 19], and in [Miles Davis and American Culture, Missouri Historical Society Press Series, Gerald Lyn, Early, Missouri History Museum, 2001, 9781883982386, 205]

1960s

About the new modal style. Interviewed by The Jazz Review, 1958; Quotes in Paul Maher, Michael K. Dorr (2009) Miles on Miles: Interviews and Encounters with Miles Davis, p. 18.

1950s