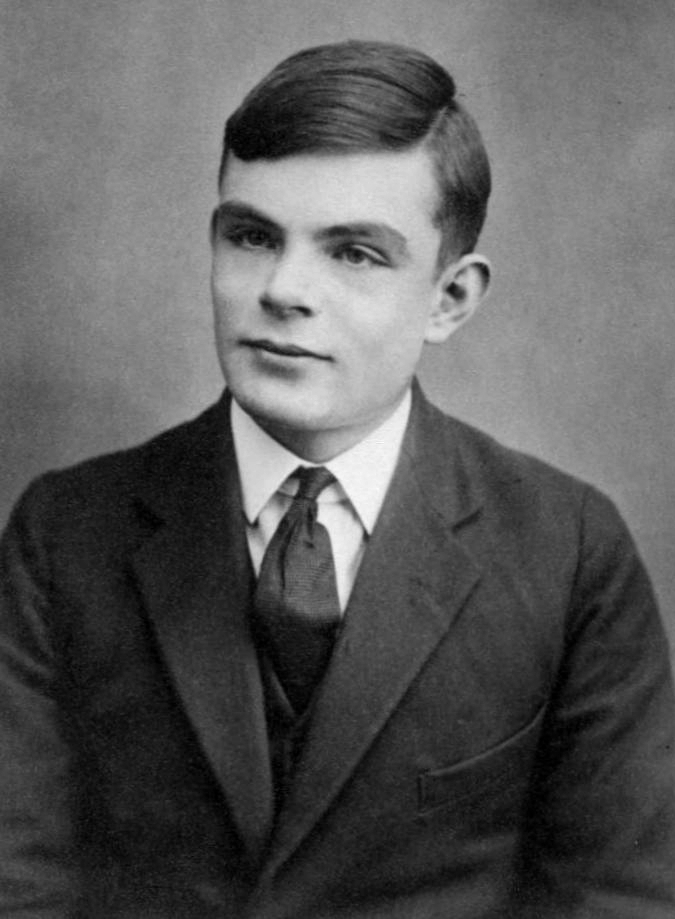

Alan Turing frasi celebri

da Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Mind 59 (1950), pagina 443.

“Possiamo vedere solo poco davanti a noi, ma possiamo vedere tante cose che bisogna fare.”

dal suo articolo sul test di Turing

Frasi su auto di Alan Turing

Mechanical Intelligence: Collected Works of A.M. Turing

Mechanical Intelligence: Collected Works of A.M. Turing

Alan Turing Frasi e Citazioni

Attribuite

Origine: Pronunciato alla mensa dei Bell Labs, 1943; citato in A. Hodges, Storia di un enigma – Alan Turing, Boringhieri.

Mechanical Intelligence: Collected Works of A.M. Turing

“La scienza è un'equazione differenziale. La religione è una condizione al contorno.”

Attribuite

Origine: Citato in J. D. Barrow, Teorie del tutto. La ricerca della spiegazione ultima.

Mechanical Intelligence: Collected Works of A.M. Turing

Alan Turing: Frasi in inglese

“Sometimes it is the people no one can imagine anything of who do the things no one can imagine.”

Variante: Sometimes it is the people who no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.

“These questions replace our original, "Can machines think?"”

Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950)

Contesto: "Can machines think?"... The new form of the problem can be described in terms of a game which we call the 'imitation game." It is played with three people, a man (A), a woman (B), and an interrogator (C) who may be of either sex. The interrogator stays in a room apart front the other two. The object of the game for the interrogator is to determine which of the other two is the man and which is the woman. He knows them by labels X and Y, and at the end of the game he says either "X is A and Y is B" or "X is B and Y is A." The interrogator is allowed to put questions to A and B... We now ask the question, "What will happen when a machine takes the part of A in this game?" Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman? These questions replace our original, "Can machines think?"

"Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals," section 11: The purpose of ordinal logics (1938), published in Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, series 2, vol. 45 (1939)

In a footnote to the first sentence, Turing added: "We are leaving out of account that most important faculty which distinguishes topics of interest from others; in fact, we are regarding the function of the mathematician as simply to determine the truth or falsity of propositions."

Contesto: Mathematical reasoning may be regarded rather schematically as the exercise of a combination of two facilities, which we may call intuition and ingenuity. The activity of the intuition consists in making spontaneous judgements which are not the result of conscious trains of reasoning... The exercise of ingenuity in mathematics consists in aiding the intuition through suitable arrangements of propositions, and perhaps geometrical figures or drawings.

“We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.”

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 460.

Origine: Computing machinery and intelligence

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 442.

Origine: Computing machinery and intelligence

“Machines take me by surprise with great frequency.”

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 450.

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 451.

Contesto: The view that machines cannot give rise to surprises is due, I believe, to a fallacy to which philosophers and mathematicians are particularly subject. This is the assumption that as soon as a fact is presented to a mind all consequences of that fact spring into the mind simultaneously with it. It is a very useful assumption under many circumstances, but one too easily forgets that it is false. A natural consequence of doing so is that one then assumes that there is no virtue in the mere working out of consequences from data and general principles.

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 454.

Contesto: Another simile would be an atomic pile of less than critical size: an injected idea is to correspond to a neutron entering the pile from without. Each such neutron will cause a certain disturbance which eventually dies away. If, however, the size of the pile is sufficiently increased, the disturbance caused by such an incoming neutron will very likely go on and on increasing until the whole pile is destroyed. Is there a corresponding phenomenon for minds, and is there one for machines? There does seem to be one for the human mind. The majority of them seem to be "sub-critical," i. e., to correspond in this analogy to piles of sub-critical size. An idea presented to such a mind will on average give rise to less than one idea in reply. A smallish proportion are super-critical. An idea presented to such a mind may give rise to a whole "theory" consisting of secondary, tertiary and more remote ideas. Animals minds seem to be very definitely sub-critical. Adhering to this analogy we ask, "Can a machine be made to be super-critical?"

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), pp. 443-444.

Contesto: I am not very impressed with theological arguments whatever they may be used to support. Such arguments have often been found unsatisfactory in the past. In the time of Galileo it was argued that the texts, "And the sun stood still... and hasted not to go down about a whole day" (Joshua x. 13) and "He laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not move at any time" (Psalm cv. 5) were an adequate refutation of the Copernican theory.

Origine: Mechanical Intelligence: Collected Works of A.M. Turing

"Proposed Electronic Calculator" (1946), a report for National Physical Laboratory, Teddington; published in A. M. Turing's ACE Report of 1946 and Other Papers (1986), edited by B. E. Carpenter and R. W. Doran, and in The Collected Works of A. M. Turing (1992), edited by D. C. Ince, Vol. 3.

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 456.

"Intelligent Machinery: A Report by A. M. Turing," (Summer 1948), submitted to the National Physical Laboratory (1948) and published in Key Papers: Cybernetics, ed. C. R. Evans and A. D. J. Robertson (1968) and, in variant form, in Machine Intelligence 5, ed. B. Meltzer and D. Michie (1969).

“Science is a differential equation. Religion is a boundary condition.”

Epigram to Robin Gandy (1954); reprinted in Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (Vintage edition 1992), p. 513.

Origine: Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950), p. 436.

On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)

On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)

“[T]he m-configuration may be changed.”

On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)

On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)

On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)

“The "scanned symbol" is the only one of which the machine is... "directly aware."”

However, by altering its m-configuration the machine can effectively remember some of the symbols which it has "seen" (scanned) previously.

On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem (1936)