Variante: Quando faccio bene mi sento bene. Quando faccio male mi sento male. Questa è la mia religione.

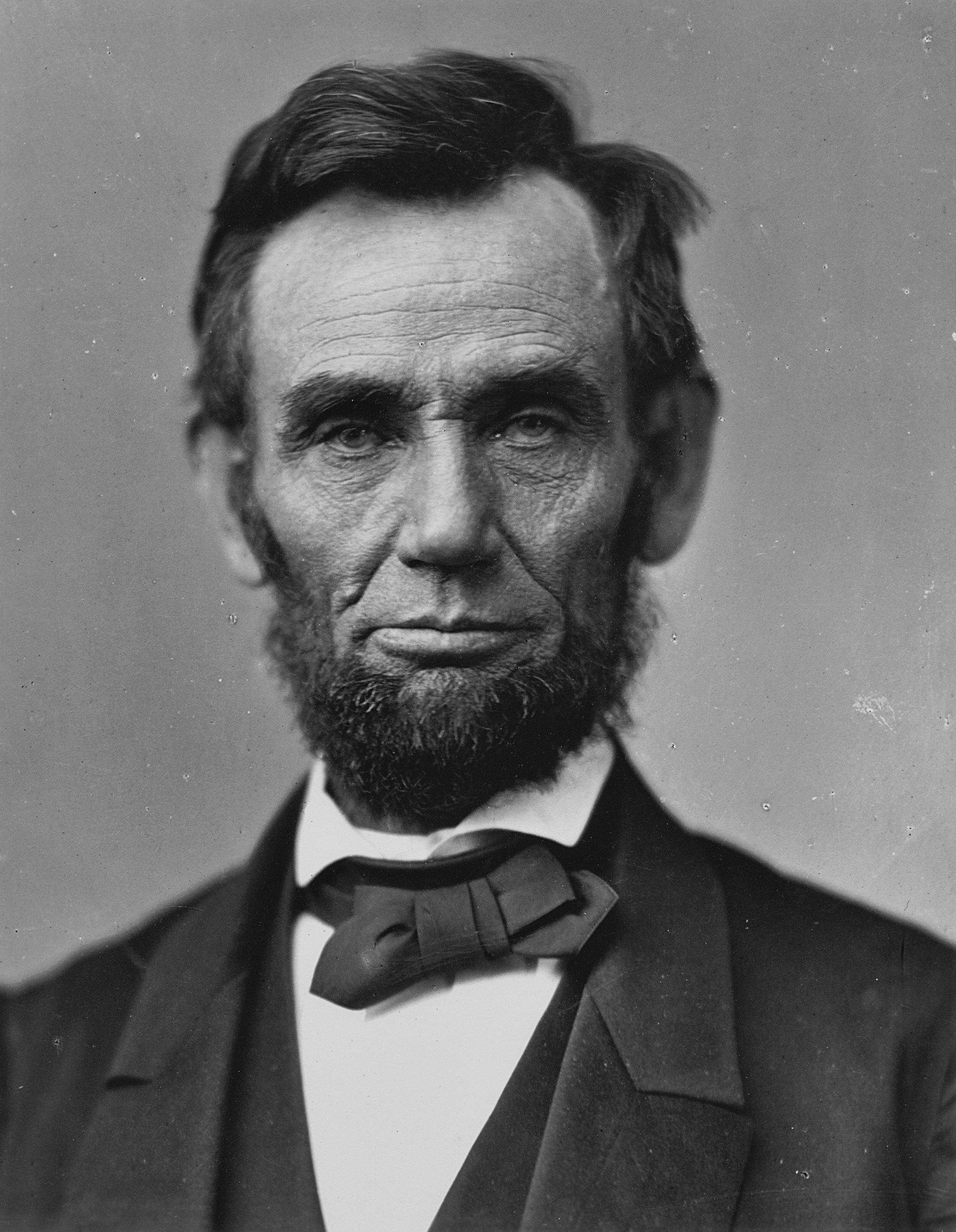

Abraham Lincoln frasi celebri

“La miglior cosa del futuro è che arriva un giorno alla volta.”

Origine: Citato in Focus, n. 113, p. 129

Frasi sulla vita di Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln Frasi e Citazioni

Origine: Da Discorso a Clinton, 1858.

Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.

[Citazione errata] La prima attribuzione ad Abraham Lincoln si trova nel Golden Book magazine del novembre 1931. La citazione è stata attribuita anche a Mark Twain e in misura minore a Confucio, John Maynard Keynes e Arthur Burns. Inoltre diversi proverbi esprimono un concetto simile, tra questi ne va ricordato uno incluso nel Libro dei Proverbi della Bibbia: «Anche lo stolto, se tace, passa per saggio | e, se tien chiuse le labbra, per intelligente.». In realtà la citazione sembrerebbe appartenere a Maurice Switzer, infatti una prima traccia di questa frase si ritrova proprio nel suo libro, Mrs. Goose, Her Book del 1907. La frase viene citata anche da Lisa nel decimo episodio della quarta stagione de I Simpson.

Attribuite

Variante: Meglio tacere e dare l'impressione di essere stupidi, piuttosto che parlare e togliere ogni dubbio!

Origine: Cfr. Better to Remain Silent and Be Thought a Fool than to Speak and Remove All Doubt http://quoteinvestigator.com/2010/05/17/remain-silent/, QuoteInvestigator.com, 17 maggio 2010.

“Nessuno ha una memoria tanto buona da poter essere un perfetto bugiardo.”

Origine: Citato in Selezione dal Redear's Digest, dicembre 1962.

Origine: Citato in John D. Barrow, I numeri dell'universo, Mondadori, 2004.

Origine: Lincoln Abraham Senate document 23, Page 91. 1865.

Origine: Citato in Aldo Grasso, Il vizio antico, fuga dal carro perdente, Corriere della Sera, 11 dicembre 2016, p. 1.

“Io credo che il più grande dono che Dio ha fatto all'umanità sia la Bibbia.”

Origine: Da The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (Rutgers University Press, 1953), ed. Roy P. Basler, volume VII, p. 542.

Origine: Citato in AA.VV., Il libro degli aforismi, Gribaudo, Milano, 2011, p. 268 http://books.google.it/books?id=PJKwfd6ulGMC&pg=PA268. Citato anche in Giuliana Rotondi, Tutti i gatti del presidente, Focus Storia , n. 70, agosto 2012, p. 61: «La religione di un uomo non è gran cosa se non ne traggono beneficio anche il cane e il gatto».

Origine: Dalla lettera del 4 aprile 1864 ad Albert G. Hodges, editore del Frankfort, Kentucky, Commonwealth (riportando la loro conversazione del 26 marzo 1864). Manuscript at The Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trt027.html; anche in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler, volume VII, p. 281.

Abraham Lincoln: Frasi in inglese

1850s, Speech at Chicago (1858)

Contesto: I believe each individual is naturally entitled to do as he pleases with himself and the fruit of his labor, so far as it in no wise interferes with any other man's rights, that each community, as a State, has a right to do exactly as it pleases with all the concerns within that State that interfere with the right of no other State, and that the general government, upon principle, has no right to interfere with anything other than that general class of things that does concern the whole.

“It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There I grew up.”

1850s, Autobiographical Sketch Written for Jesse W. Fell (1859)

Contesto: My father, at the death of his father, was but six years of age, and he grew up literally without education. He removed from Kentucky to what is now Spencer County, Indiana, in my eighth year. We reached our new home about the time the State came into the Union. It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There I grew up.<!--p.33

1860s, Reply to an Emancipation Memorial (1862)

Contesto: The subject presented in the memorial is one upon which I have thought much for weeks past, and I may even say for months. I am approached with the most opposite opinions and advice, and that by religious men, who are equally certain that they represent the Divine will. I am sure that either the one or the other class is mistaken in that belief, and perhaps in some respects both. I hope it will not be irreverent for me to say that if it is probable that God would reveal his will to others, on a point so connected with my duty, it might be supposed he would reveal it directly to me; for, unless I am more deceived in myself than I often am, it is my earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter. And if I can learn what it is I will do it! These are not, however, the days of miracles, and I suppose it will be granted that I am not to expect a direct revelation. I must study the plain physical facts of the case, ascertain what is possible, and learn what appears to be wise and right.

The subject is difficult, and good men do not agree.

“Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper.”

1860s, Cooper Union speech (1860)

Contesto: It is exceedingly desirable that all parts of this great Confederacy shall be at peace, and in harmony, one with another. Let us Republicans do our part to have it so. Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper. Even though the southern people will not so much as listen to us, let us calmly consider their demands, and yield to them if, in our deliberate view of our duty, we possibly can.

“Gold is good in its place; but living, brave, and patriotic men are better than gold.”

1860s, On Democratic Government (1864)

Contesto: But the election, along with its incidental and undesirable strife, has done good, too. It has demonstrated that a people's government can sustain a national election in the midst of a great civil war. Until now, it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows, also, how sound and strong we still are. It shows that even among the candidates of the same party, he who is most devoted to the Union and most opposed to treason can receive most of the people's votes. It shows, also, to the extent yet known, that we have more men now than we had when the war began. Gold is good in its place; but living, brave, and patriotic men are better than gold.

1860s, Cooper Union speech (1860)

Contesto: Human action can be modified to some extent, but human nature cannot be changed. There is a judgment and a feeling against slavery in this nation, which cast at least a million and a half of votes. You cannot destroy that judgment and feeling — that sentiment — by breaking up the political organization which rallies around it. You can scarcely scatter and disperse an army which has been formed into order in the face of your heaviest fire; but if you could, how much would you gain by forcing the sentiment which created it out of the peaceful channel of the ballot-box, into some other channel?

Letter, while US Congressman, to his friend and law-partner William H. Herndon, opposing the Mexican-American War (15 February 1848)

1840s

Contesto: Allow the President to invade a neighboring nation, whenever he shall deem it necessary to repel an invasion, and you allow him to do so, whenever he may choose to say he deems it necessary for such purpose, and you allow him to make war at pleasure. Study to see if you can fix any limit to his power in this respect, after having given him so much as you propose. If, to-day, he should choose to say he thinks it necessary to invade Canada, to prevent the British from invading us, how could you stop him? You may say to him, "I see no probability of the British invading us" but he will say to you, "Be silent; I see it, if you don't."

The provision of the Constitution giving the war making power to Congress was dictated, as I understand it, by the following reasons. Kings had always been involving and impoverishing their people in wars, pretending generally, if not always, that the good of the people was the object. This, our Convention understood to be the most oppressive of all Kingly oppressions; and they resolved to so frame the Constitution that no one man should hold the power of bringing this oppression upon us. But your view destroys the whole matter, and places our President where kings have always stood.

Speech at Edwardsville, Illinois (11 September 1858); quoted in Lincoln, Abraham; Mario Matthew Cuomo, Harold Holzer, G. S. Boritt, Lincoln on Democracy http://books.google.de/books?id=8bWmmyJEMZoC&pg=PA128 (Fordham University Press, September 1, 2004), 128. .

Variant of the above quote: What constitutes the bulwark of our own liberty and independence? It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling sea coasts, our army and our navy. These are not our reliance against tyranny All of those may be turned against us without making us weaker for the struggle. Our reliance is in the love of liberty which God has planted in us. Our defense is in the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands everywhere. Destroy this spirit and you have planted the seeds of despotism at your own doors. Familiarize yourselves with the chains of bondage and you prepare your own limbs to wear them. Accustomed to trample on the rights of others, you have lost the genius of your own independence and become the fit subjects of the first cunning tyrant who rises among you.

Fragment of Speech at Edwardsville, Ill., September 13, 1858; quoted in Lincoln, Abraham; The Writings of Abraham Lincoln V05 http://www.classic-literature.co.uk/american-authors/19th-century/abraham-lincoln/the-writings-of-abraham-lincoln-05/ebook-page-05.asp) p. 6-7

1850s

Contesto: What constitutes the bulwark of our own liberty and independence? It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling sea coasts, the guns of our war steamers, or the strength our gallant and disciplined army? These are not our reliance against a resumption of tyranny in our fair land. All of those may be turned against our liberties, without making us weaker or stronger for the struggle. Our reliance is in the love of liberty which God has planted in our bosoms. Our defense is in the preservation of the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands, everywhere. Destroy this spirit, and you have planted the seeds of despotism around your own doors. Familiarize yourselves with the chains of bondage and you are preparing your own limbs to wear them. Accustomed to trample on the rights of those around you, you have lost the genius of your own independence, and become the fit subjects of the first cunning tyrant who rises.

Origine: 1860s, Second State of the Union address (1862)

Contesto: Labor is like any other commodity in the market — increase the demand for it and you increase the price of it. Reduce the supply of black labor by colonizing the black laborer out of the country, and by precisely so much you increase the demand for and wages of white labor.

1860s, Illinois Farewell Address (1861)

Contesto: My friends — No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe every thing. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of that Divine Being, who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him, who can go with me, and remain with you and be every where for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To His care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.

1850s, Speech at Peoria, Illinois (1854)

Contesto: "Fools rush in where angels fear to tread." At the hazard of being thought one of the fools of this quotation, I meet that argument — I rush in — I take that bull by the horns. I trust I understand and truly estimate the right of self-government. My faith in the proposition that each man should do precisely as he pleases with all which is exclusively his own lies at the foundation of the sense of justice there is in me. I extend the principle to communities of men as well as to individuals. I so extend it because it is politically wise, as well as naturally just: politically wise in saving us from broils about matters which do not concern us. Here, or at Washington, I would not trouble myself with the oyster laws of Virginia, or the cranberry laws of Indiana. The doctrine of self-government is right, — absolutely and eternally right, — but it has no just application as here attempted. Or perhaps I should rather say that whether it has such application depends upon whether a negro is not or is a man. If he is not a man, in that case he who is a man may as a matter of self-government do just what he pleases with him.

But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent a total destruction of self-government to say that he too shall not govern himself. When the white man governs himself, that is self-government; but when he governs himself and also governs another man, that is more than self-government — that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that "all men are created equal," and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man's making a slave of another.

1860s, Thanksgiving Proclamation (1863)

Contesto: The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God.

This they said, and this meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, nor yet, that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit. They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere. The assertion that "all men are created equal" was of no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain; and it was placed in the Declaration, nor for that, but for future use. Its authors meant it to be, thank God, it is now proving itself, a stumbling block to those who in after times might seek to turn a free people back into the hateful paths of despotism. They knew the proneness of prosperity to breed tyrants, and they meant when such should re-appear in this fair land and commence their vocation they should find left for them at least one hard nut to crack. I have now briefly expressed my view of the meaning and objects of that part of the Declaration of Independence which declares that "all men are created equal".

1850s, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision (1857)

1860s, Cooper Union speech (1860)

1860s

Contesto: In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. The older have learned to ever expect it. I am anxious to afford some alleviation of your present distress. Perfect relief is not possible, except with time. You can not now realize that you will ever feel better. Is not this so? And yet it is a mistake. You are sure to be happy again. To know this, which is certainly true, will make you some less miserable now. I have had experience enough to know what I say; and you need only to believe it, to feel better at once.

Letter to Fanny McCullough (23 December 1862); Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy P. Basler

1860s, Cooper Union speech (1860)

Contesto: But you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that supposed event, you say, you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us! That is cool. A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, "Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you, and then you will be a murderer!" To be sure, what the robber demanded of me — my money — was my own; and I had a clear right to keep it; but it was no more my own than my vote is my own; and the threat of death to me, to extort my money, and the threat of destruction to the Union, to extort my vote, can scarcely be distinguished in principle.

1850s, Speech at Peoria, Illinois (1854)

Contesto: Little by little, but steadily as man's march to the grave, we have been giving up the OLD for the NEW faith. Near eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for SOME men to enslave OTHERS is a “sacred right of self-government.” These principles can not stand together. They are as opposite as God and mammon; and whoever holds to the one, must despise the other. [... ] Let no one be deceived. The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms; and the former is being rapidly displaced by the latter.

1860s, Speeches to Ohio Regiments (1864), Speech to One Hundred Forty-eighth Ohio Regiment (1864)

Contesto: It is vain and foolish to arraign this man or that for the part he has taken, or has not taken, and to hold the government responsible for his acts. In no administration can there be perfect equality of action and uniform satisfaction rendered by all. But this government must be preserved in spite of the acts of any man or set of men. It is worthy your every effort. Nowhere in the world is presented a government of so much liberty and equality. To the humblest and poorest amongst us are held out the highest privileges and positions. The present moment finds me at the White House, yet there is as good a chance for your children as there was for my father's.

1860s, Allow the humblest man an equal chance (1860)

Contesto: These natural and apparently adequate means all failing, what will convince them? This, and this only; cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right. And this must be done thoroughly — done in acts as well as in words. Silence will not be tolerated — we must place ourselves avowedly with them. Douglas's new sedition law must be enacted and enforced, suppressing all declarations that Slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with greedy pleasure. We must pull down our Free State Constitutions. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected of all taint of opposition to Slavery, before they will cease to believe that all their troubles proceed from us. So long as we call Slavery wrong, whenever a slave runs away they will overlook the obvious fact that he ran because he was oppressed, and declare he was stolen off. Whenever a master cuts his slaves with the lash, and they cry out under it, he will overlook the obvious fact that the negroes cry out because they are hurt, and insist that they were put up to it by some rascally abolitionist.

1850s, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision (1857)

Contesto: We believe … in obedience to, and respect for the judicial department of government. We think its decisions on Constitutional questions, when fully settled, should control, not only the particular cases decided, but the general policy of the country, subject to be disturbed only by amendments of the Constitution as provided in that instrument itself. More than this would be revolution. But we think the Dred Scott decision is erroneous. … If this important decision had been made by the unanimous concurrence of the judges, and without any apparent partisan bias, and in accordance with legal public expectation, and with the steady practice of the departments throughout our history, and had been in no part, based on assumed historical facts which are not really true; or, if wanting in some of these, it had been before the court more than once, and had there been affirmed and re-affirmed through a course of years, it then might be, perhaps would be, factious, nay, even revolutionary, to not acquiesce in it as a precedent.

1860s, "If Slavery Is Not Wrong, Nothing Is Wrong" (1864)

Contesto: In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation's condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God.

1860s, Speeches to Ohio Regiments (1864), Speech to the One Hundred Sixty-fourth Ohio Regiment

Contesto: I say this in order to impress upon you, if you are not already so impressed, that no small matter should divert us from our great purpose. There may be some irregularities in the practical application of our system. It is fair that each man shall pay taxes in exact proportion to the value of his property; but if we should wait before collecting a tax to adjust the taxes upon each man in exact proportion with every other man, we should never collect any tax at all. There may be mistakes made sometimes; things may be done wrong while the officers of the Government do all they can to prevent mistakes. But I beg of you, as citizens of this great Republic, not to let your minds to carried off from the great work we have before us. This struggle is too large for you to be diverted from it by any small matter.

Speech in Reply to Senator Stephen Douglas in the Lincoln-Douglas debates http://www.bartleby.com/251/1003.html of the 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate, at Chicago, Illinois (10 July 1858)

1850s, Lincoln–Douglas debates (1858)

Contesto: Now, it happens that we meet together once every year, sometimes about the fourth of July, for some reason or other. These fourth of July gatherings I suppose have their uses. … We are now a mighty nation; we are thirty, or about thirty, millions of people, and we own and inhabit about one-fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years, and we discover that we were then a very small people in point of numbers, vastly inferior to what we are now, with a vastly less extent of country, with vastly less of everything we deem desirable among men; we look upon the change as exceedingly advantageous to us and to our posterity, and we fix upon something that happened away back, as in some way or other being connected with this rise of prosperity. We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men; they fought for the principle that they were contending for; and we understood that by what they then did it has followed that the degree of prosperity which we now enjoy has come to us. We hold this annual celebration to remind ourselves of all the good done in this process of time, of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it; and we go from these meetings in better humor with ourselves, we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way we are better men in the age, and race, and country in which we live, for these celebrations. But after we have done all this we have not yet reached the whole. There is something else connected with it. We have besides these, men descended by blood from our ancestors — among us, perhaps half our people, who are not descendants at all of these men; they are men who have come from Europe — German, Irish, French and Scandinavian — men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here, finding themselves our equals in all things. If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us, but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence, they find that those old men say that "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal" and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh, of the men who wrote that Declaration; and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.

1860s, Allow the humblest man an equal chance (1860)

Contesto: It is easy to demonstrate that "our Fathers, who framed this government under which we live," looked on Slavery as wrong, and so framed it and everything about it as to square with the idea that it was wrong, so far as the necessities arising from its existence permitted. In forming the Constitution they found the slave trade existing; capital invested in it; fields depending upon it for labor, and the whole system resting upon the importation of slave-labor. They therefore did not prohibit the slave trade at once, but they gave the power to prohibit it after twenty years. Why was this? What other foreign trade did they treat in that way? Would they have done this if they had not thought slavery wrong? Another thing was done by some of the same men who framed the Constitution, and afterwards adopted as their own act by the first Congress held under that Constitution, of which many of the framers were members; they prohibited the spread of Slavery into Territories. Thus the same men, the framers of the Constitution, cut off the supply and prohibited the spread of Slavery, and both acts show conclusively that they considered that the thing was wrong. If additional proof is wanting it can be found in the phraseology of the Constitution. When men are framing a supreme law and chart of government, to secure blessings and prosperity to untold generations yet to come, they use language as short and direct and plain as can be found, to express their meaning. In all matters but this of Slavery the framers of the Constitution used the very clearest, shortest, and most direct language. But the Constitution alludes to Slavery three times without mentioning it once! The language used becomes ambiguous, roundabout, and mystical. They speak of the "immigration of persons," and mean the importation of slaves, but do not say so. In establishing a basis of representation they say "all other persons," when they mean to say slaves — why did they not use the shortest phrase? In providing for the return of fugitives they say "persons held to service or labor." If they had said slaves it would have been plainer, and less liable to misconstruction. Why didn't they do it. We cannot doubt that it was done on purpose. Only one reason is possible, and that is supplied us by one of the framers of the Constitution — and it is not possible for man to conceive of any other — they expected and desired that the system would come to an end, and meant that when it did, the Constitution should not show that there ever had been a slave in this good free country of ours!

1850s, Autobiographical Sketch Written for Jesse W. Fell (1859)

Contesto: In 1846 I was once elected to the lower House of Congress. Was not a candidate for reëlection. From 1849 to 1854, both inclusive, practiced law more assiduously than ever before. Always a Whig in politics; and generally on the Whig electoral tickets making active canvasses. I was losing interest in politics when the repeal of the aroused me again. What I have done since then is pretty well known.<!--pp.35-36

1860s, Fourth of July Address to Congress (1861)

Contesto: Our popular Government has often been called an experiment. Two points in it our people have already settled — the successful establishing and the successful administering of it. One still remains — its successful maintenance against a formidable internal attempt to overthrow it. It is now for them to demonstrate to the world that those who can fairly carry an election can also suppress a rebellion; that ballots are the rightful and peaceful successors of bullets, and that when ballots have fairly and constitutionally decided there can be no successful appeal back to bullets; that there can be no successful appeal except to ballots themselves at succeeding elections. Such will be a great lesson of peace, teaching men that what they can not take by an election neither can they take it by a war; teaching all the folly of being the beginners of a war.

In some trifling particulars, the condition of that race has been ameliorated; but, as a whole, in this country, the change between then and now is decidedly the other way; and their ultimate destiny has never appeared so hopeless as in the last three or four years. In two of the five states — New Jersey and North Carolina — that then gave the free negro the right of voting, the right has since been taken away; and in a third — New York — it has been greatly abridged; while it has not been extended, so far as I know, to a single additional state, though the number of the States has more than doubled.

1850s, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision (1857)

1860s, Reply to an Emancipation Memorial (1862)

Contesto: The subject presented in the memorial is one upon which I have thought much for weeks past, and I may even say for months. I am approached with the most opposite opinions and advice, and that by religious men, who are equally certain that they represent the Divine will. I am sure that either the one or the other class is mistaken in that belief, and perhaps in some respects both. I hope it will not be irreverent for me to say that if it is probable that God would reveal his will to others, on a point so connected with my duty, it might be supposed he would reveal it directly to me; for, unless I am more deceived in myself than I often am, it is my earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter. And if I can learn what it is I will do it! These are not, however, the days of miracles, and I suppose it will be granted that I am not to expect a direct revelation. I must study the plain physical facts of the case, ascertain what is possible, and learn what appears to be wise and right.

The subject is difficult, and good men do not agree.

1860s, Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction (1863)

1860s, Cooper Union speech (1860)

Contesto: But you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that supposed event, you say, you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us! That is cool. A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, "Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you, and then you will be a murderer!" To be sure, what the robber demanded of me — my money — was my own; and I had a clear right to keep it; but it was no more my own than my vote is my own; and the threat of death to me, to extort my money, and the threat of destruction to the Union, to extort my vote, can scarcely be distinguished in principle.